For centuries, childbirth has been a profound yet challenging journey, often accompanied by serious complications for both mother and child. In the late 16th century, a procedure known as symphysiotomy emerged as a desperate measure to assist with difficult births. This intense practice, involving the separation of a woman’s pelvic joint to widen the birth canal, persisted in some regions—most notably Ireland—well into the 20th century. Remarkably, the chainsaw, now known as a tool in other contexts, was originally invented to aid in this distressing procedure. This is the sobering history of symphysiotomy, a medical intervention that left many women deeply affected.

The Origins of a Harsh Practice

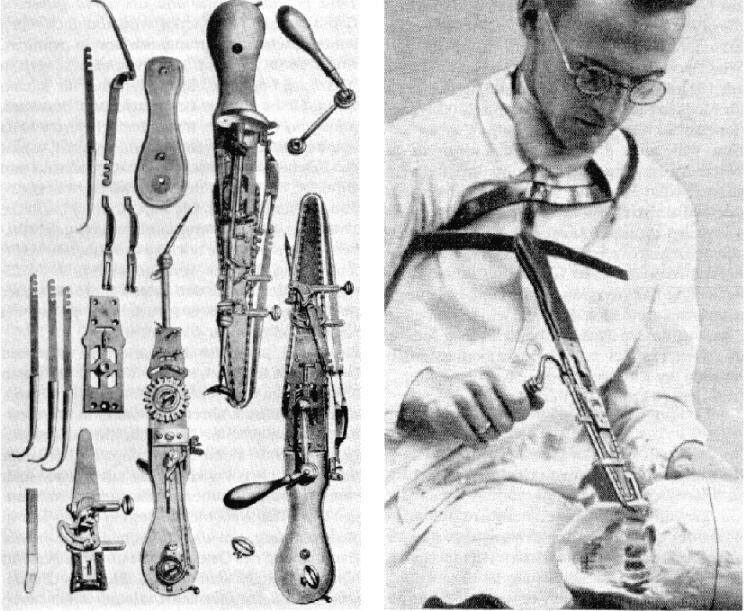

The symphysiotomy dates back to around 1597, when early physicians, facing the dangers of childbirth, developed a method to manually divide the cartilage and ligaments of a woman’s pubic symphysis joint. This joint connects the two halves of the pelvis, and separating it allowed the pelvis to expand, creating more space for an infant to pass through the birth canal. However, the procedure was laborious, painful, and imprecise, relying on basic tools that made it a grueling experience.

By the late 18th century, the process became more efficient with the invention of a chainsaw-like device. Scottish doctor John Aitken, in his 1785 work Principles of Midwifery or Puerperal Medicine, described a tool designed to divide the pelvic joint more effectively. Around the same time, another physician, James Jeffray, developed a similar medical chainsaw for removing diseased bone. These early chainsaws were far from modern tools, but their purpose was clear: to make symphysiotomies quicker, if not less painful.

In the 19th century, symphysiotomies were seen as a safer alternative to Cesarean sections, which carried a high risk of infection and complications before modern surgical techniques. The procedure, though harsh, was considered a necessary measure to save mothers and babies when vaginal delivery was not possible.

A Persistent Practice in Ireland

As medical advancements in the 20th century made Cesarean sections safer and more reliable, symphysiotomies fell out of favor across most of the Western world. But in Ireland, the procedure remained a common practice until the 1980s. The reasons are complex and debated. Some attribute its persistence to the influence of Catholicism, which disapproved of interventions like Cesarean sections that might limit future pregnancies or require contraception—both at odds with religious doctrine. Others argue that medical conservatism, rather than religion, kept the procedure in use.

Whatever the cause, the experiences of Irish women who underwent symphysiotomies reveal a story of profound suffering. Without adequate anesthesia, many endured the procedure fully conscious, restrained, and in severe pain. Philomena, who underwent a symphysiotomy in 1959, recounted to CNN the distress of being “operated on” in a packed operating theater: “I was screaming and being restrained… I couldn’t see much except for them working. It was unbearable pain.”

Cora, just 17 when she gave birth in 1972, described a similarly harrowing scene to The Guardian: “I was screaming. It’s not working, [the anesthetic], I said, I can feel everything… I saw him go and take out a proper saw, like a carpenter’s tool… The blood surged upward, onto his glasses, all over the nurses.” She recalled the surgeon using a tool like a soldering iron to stop the bleeding, leaving her convinced she was in mortal danger.

The Lasting Impact on Survivors

The physical and emotional effects of symphysiotomy were profound. Women reported chronic health issues, including incontinence, persistent pain, and early-onset arthritis. For many, the trauma lingered for decades, contributing to miscarriages and a deep sense of violation. Rita McCann, who underwent the procedure in 1957, told The Guardian in 2014: “I feel deep frustration that it wasn’t explained, we weren’t given any options… No one could talk about it without breaking down in tears.”

The lack of informed consent was a recurring theme among survivors. Many women were not told what was happening to them, left to endure the procedure in confusion and fear. The psychological impact was so severe that some, like McCann, struggled to process the memories, even years later. “You try to move past a lot of it,” she said, “but you don’t forget. It left me shaken.”

The Legacy and Decline of Symphysiotomy

By the late 20th century, symphysiotomy had largely disappeared from modern medicine in the Western world, replaced by safer and less invasive options like Cesarean sections. A 2010 study in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews described the procedure as a “second-best” option, though it remains a rare, life-saving measure in resource-poor settings where advanced surgical care is unavailable.

In Ireland, the procedure’s troubling legacy prompted action. In 2016, the government awarded compensation of €50,000 to €150,000 to hundreds of women who had endured symphysiotomies. Yet for many, the financial redress could not erase the physical and emotional toll. Survivors demanded not just compensation but accountability—an apology and an explanation for why they were subjected to such a painful procedure without consent.

From Childbirth to Chainsaws

Remarkably, the chainsaw, born out of the need to perform symphysiotomies, found a new purpose far removed from the operating room. In 1905, American Samuel J. Bens patented an electric chainsaw designed to fell massive redwood trees. By the 1920s, German engineer Andreas Stihl introduced the handheld chainsaw, a tool that revolutionized forestry and became widely recognized—though now more associated with other uses than with medicine.

Today, the idea of using a chainsaw in childbirth is unimaginable, a relic of a less advanced era. Modern obstetrics prioritizes the safety and dignity of mothers and babies, with Cesarean sections and other interventions offering far less distressing solutions. Yet for the women who survived symphysiotomies, the procedure remains a haunting reminder of a time when medicine could be as challenging as the conditions it sought to address.