Francis Ford Coppola and His Attachment to Cars From Birth to His Passion for Tucker ’48

Francis Ford Coppola’s relationship with cars began when he was born, or even before. He was born at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, and Henry Ford sometimes attended rehearsals of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, where Coppola’s father first played the flute. The Godfather director explained: “Following the family tradition of giving a middle name to an important family acquaintance, they named me ‘Ford’.”But Coppola soon came to admire a lesser-known automotive icon: Preston Tucker, father of the ill-fated ’48 Tucker, a cutting-edge car that was never mass-produced because of legal troubles. and the inventor’s finances.

“When I was a kid, my dad told me about the new Tucker,” Coppola recalls. “He ordered one and invested in Tucker stock. He took me to see the car when it was on display and I was so excited. I remember the details vividly and kept asking for months, ‘When is Tucker coming?’ Finally he said it would never come, and the big companies didn’t want it to exist and wouldn’t let Mr. Tucker buy the steel or the supplies he needed.”

Coppola’s father lost a $5,000 investment, a huge sum for a middle-class man in the 1940s, but “he didn’t blame Tucker. He loves innovation.” And for Coppola, the Tucker car has become “something of a legend.” Nearly 40 years later, Coppola directed “Tucker: The Man and His Dream,” a critical success that, in Tucker tradition, failed to make money.

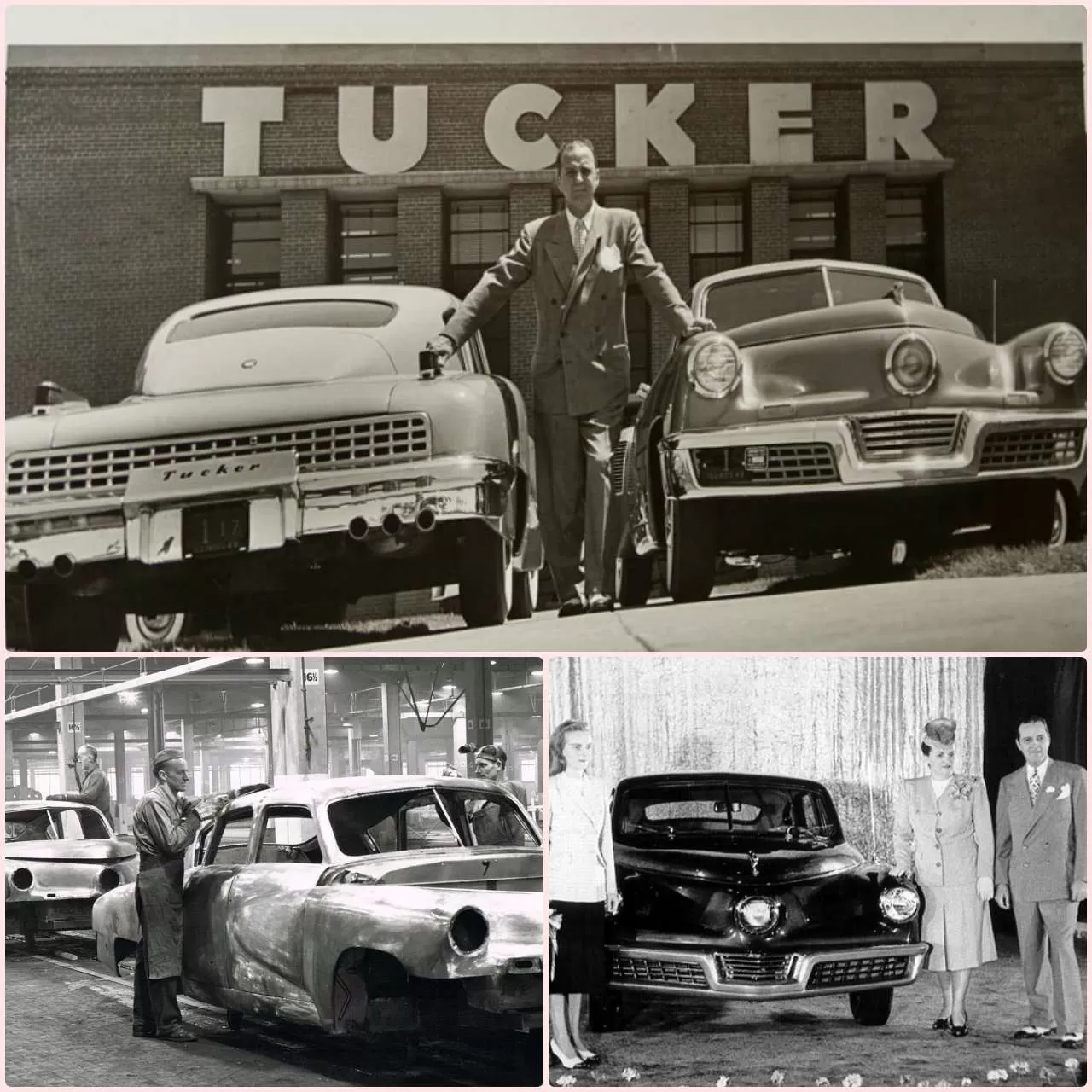

Today, Tucker’s 475-acre Chicago manufacturing plant houses a Tootsie Roll factory and shopping center. But 47 of the original 51 cars built there still exist in collections scattered around the world. Parked in the warehouse of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, No. 1039 is champagne-colored. Usually on blocks and absorbing all liquid except oil, it still emits a vivid light, like a pearl.

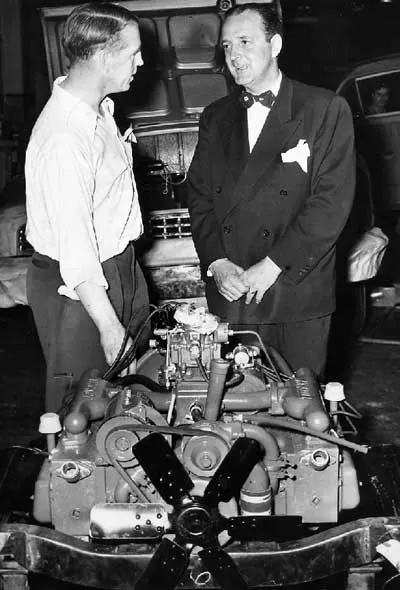

Preston Tucker, an affable character who disliked wearing a tie, was a Prohibition-era cop famous for chasing troublemakers in Lincoln Park, Michigan. One cold winter, he burned a hole in the dashboard of his unheated cruiser to channel warmth from under the hood, was demoted for his troubles and left the force. He later built racing cars and the Tucker Turret, a rotating machine gun turret used in World War II.After the war and years of sugar and meat restrictions, Americans’ greatest need was for cars. They were a cornerstone of the emerging suburban culture, but production ceased completely between 1942 and 1945, as auto factories churned out bomber engines and other wartime goods. . There were long waiting lists for new cars, and consumers spent money sight-seeing. But the first models produced in 1946 all had outdated pre-war designs. Tucker knew he could overcome them.“Tucker sees the car as a malleable object,” said Roger White, NMAH’s curator. “He was like Frank Lloyd Wright in that sense, not afraid to start from scratch.”

Unveiled in 1946 in a series of sketches, the Tucker Torpedo, as the sedan was known, jumped straight into the future: With its curvy lines, the car looked almost in motion, even when standing still. “It was like the Star Wars of its day,” said Jay Follis, historian for the Tucker Automobile Club of America. “It wasn’t just the sleek styling that resonated: The car also had Innovations include a third center headlight, which can rotate to illuminate corners; swivel fenders for protection when the vehicle turns; pop-out brake discs (designed to eject on impact). collision, passenger protection); a rear engine; and a padded dashboard.

But while his designs and safety innovations were pioneering, Tucker’s business model lagged behind. Automobile production shrank during the Great Recession; By the late 1940s, only a handful of companies remained, rooted in a culture that valued corporate prudence over individual genius. By the mid-1950s, Ford, General Motors and Chrysler produced 95 percent of America’s cars.

Tucker refused to cede creative control to the entrepreneurs who could make Tucker ’48 commercially viable. Instead, he tried to raise money through unconventional means, including selling dealership rights to a car that didn’t yet exist. The Securities and Exchange Commission investigated, he was tried for fraud, and although he was acquitted in 1950, he went bankrupt. Tucker also believes that auto industry rivals orchestrated his downfall. He died a few years later bankrupt but still working on new designs. Some considered him a fraud, others considered him a tragic visionary. (When a Tucker went up for sale this year, it fetched $2.9 million.)

“If someone has a beautiful dream but doesn’t know how to realize it, is that person a great person?” asked Roger White. “Whether Tucker was a great man or not, he was the quintessential American.”Coppola, who is currently living in China working on a new project, believes that “We are a country of innovators, but we do not always welcome or support them in their work. ” A man whose vision was sometimes stymied, Coppola says he participated in the Hollywood version of a “Tucker enterprise,” where earthly concerns prevail and great ideas reside. scattered across the cutting room floor.Whether Tucker truly started automotive history will never be known. Test drives of his inventions received mixed reviews. Coppola today owns two restored Tuckers. Even though the cars “drive like boats,” he said, they are “fast and fun.”