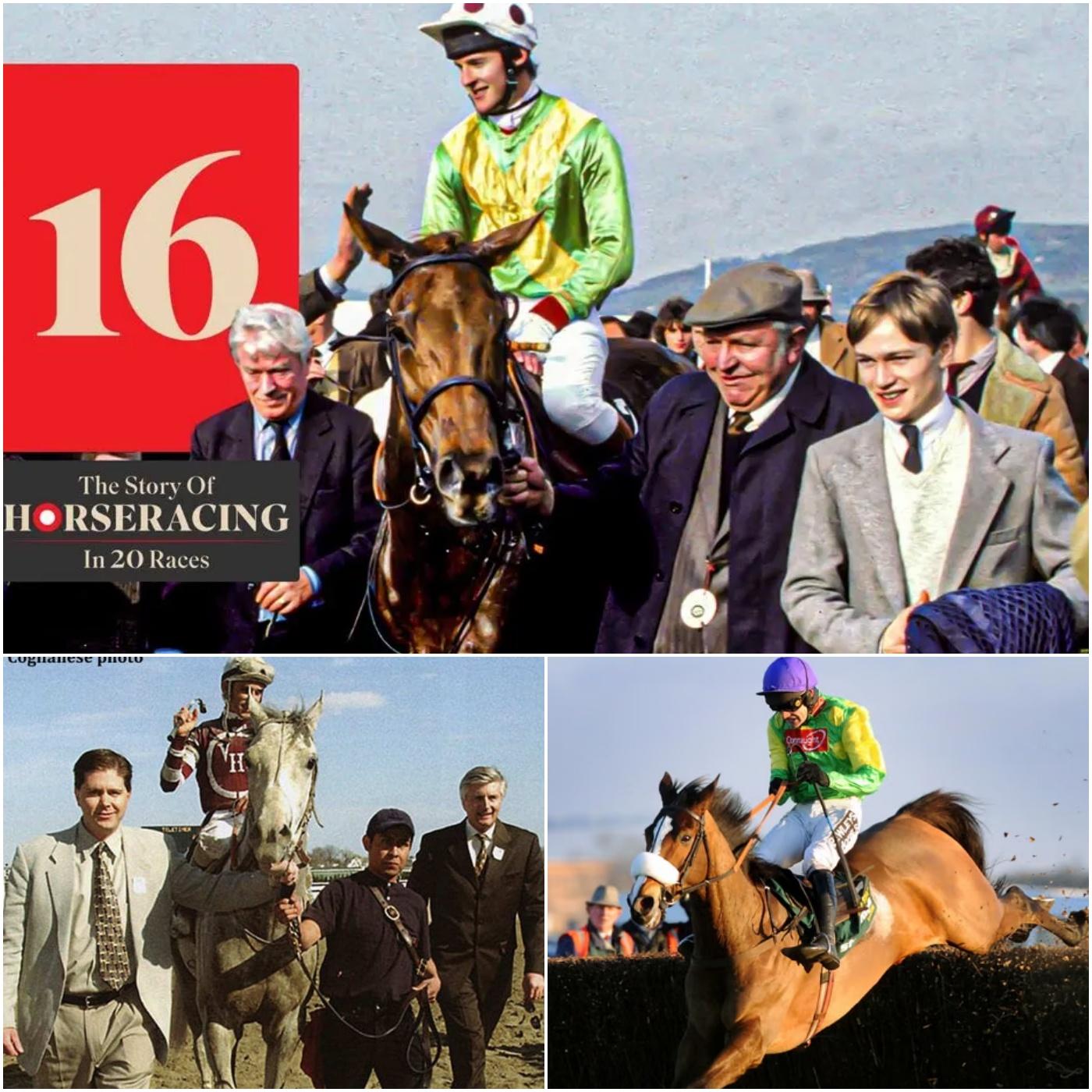

Peter Thomas Tells the Story of the Greatest Training Achievement of All Time – and Why It Put the Visionary Through ‘Hell on Earth’ at the 1983 Cheltenham Gold Cup

The Unprecedented Triumph: A Trainer’s Clean Sweep

In the annals of National Hunt racing, few moments shine as brightly—or improbably—as March 17, 1983, at Cheltenham Racecourse. Michael Dickinson, the visionary trainer from Harewood, Yorkshire, orchestrated what remains the most extraordinary feat in the history of the Cheltenham Gold Cup: saddling the first five finishers in the sport’s blue-riband event. Bregawn, ridden by a 19-year-old Graham Bradley, stormed to victory by a neck from stablemate Captain John, with Wayward Lad third, the previous year’s winner Silver Buck fourth, and Ashley House fifth. It was a domination so complete that BBC commentator Sir Peter O’Sullevan could scarcely believe his eyes, declaring it “an unprecedented Michael Dickinson quartet” before the fifth horse crossed the line. For Dickinson, then just 33, this wasn’t mere luck; it was the culmination of ruthless preparation, bold gambles, and an unyielding belief in his methods. Yet, as he later recounted in vivid detail, the path to this glory was a descent into what he called “hell on earth.”

The Making of a Mastermind: Dickinson’s Rise from Yorkshire Roots

Michael Dickinson didn’t emerge from the polished stables of the racing elite. Born into a family of Yorkshire farmers, he apprenticed under his father, Tony, a respected trainer, before striking out on his own in 1979. By 1983, his yard at Dunkeswick Grange housed over 100 horses, a mix of precocious talents and battle-hardened chasers. Dickinson’s philosophy was revolutionary for the era: data-driven, with meticulous tracking of every gallop, feed ration, and recovery session. He treated training like a science, incorporating veterinary insights and psychological conditioning long before they became commonplace. “We weren’t just running horses; we were engineering performances,” Dickinson reflected in a 2010 interview with Racing Post. His string included stars like the flamboyant Wayward Lad, a dual King George VI Chase winner, and the iron-willed Silver Buck. But entering the 1983 Gold Cup, Dickinson faced a dilemma. With five contenders in a field of 12, he knew the race would test not just their stamina over 3 miles 2½ furlongs and 22 fences, but his own nerve. To peak them all simultaneously meant skimping on prep for some—risking burnout or breakdown.

Hell on Earth: The Grueling Winter of Preparation

What Dickinson hasn’t shied away from in retellings is the personal toll. “It was hell on earth,” he admitted in a 2023 retrospective podcast with The Final Furlong, his voice still laced with the exhaustion of those months. The winter of 1982-83 was brutal: relentless rain turned gallops into quagmires, and a flu outbreak swept through the yard, sidelining key staff. Dickinson, a teetotaler with a work ethic bordering on obsessive, barely slept. He rose at 4 a.m. to oversee early feeds, then drilled his team through fog-shrouded mornings, analyzing splits from training watches to the second. Silver Buck and Wayward Lad, his blue-eyed boys, arrived undercooked after minor setbacks—Silver Buck nursing a bruised fetlock, Wayward Lad recovering from a virus. “I sent two of my best horses out half-fit, knowing they might never forgive me,” Dickinson confessed. The pressure mounted as media scrutiny intensified; whispers of overambition dogged him, with rivals like Fred Winter labeling it “hubris.” Internally, the yard fractured under the strain—grooms quit, and Dickinson’s marriage buckled under the long absences. Yet, he pushed on, fine-tuning Bregawn, a rangy seven-year-old with untapped stamina, as his unlikely spearhead. By race week, Dickinson was a shadow: gaunt, chain-smoking, haunted by the what-ifs. “You don’t train five Gold Cup horses without staring into the abyss,” he said. “I saw careers ending, dreams shattering—mine included.”

The Day of Reckoning: Cheltenham’s Roar and a Finish for the Ages

Gold Cup Day dawned crisp and clear, the Cleeve Hill crowd swelling to 50,000 under a pale March sun. Bregawn, at 100/30 favorite, jumped the first like a stag, Bradley’s cool head holding him to a rhythm that conserved energy for the infamous uphill finish. As the field turned for home, Dickinson’s quintet fanned out: Bregawn led, Captain John (ridden by the veteran John White) loomed on the rail, Wayward Lad surged wide under Colin Morse, Silver Buck tracked quietly, and Ashley House brought up the rear. The drama peaked at the second-last fence, where four of them jumped in unison—a tableau of synchronized power that left outsiders flailing. Up the hill, Bregawn dug deep, repelling Captain John’s late charge by a neck in 6:53.2, with Wayward Lad 6½ lengths back in third. Silver Buck and Ashley House plugged on for fourth and fifth, completing the lockout. The crowd erupted; Dickinson, watching from the unsaddling enclosure, collapsed into tears. “It was like waking from a nightmare,” he later wrote in his autobiography No Day Off. Prize money topped £50,000—a fortune then—but the real victory was vindication. Jenny Pitman, who would win the 1984 Gold Cup with Burrough Hill Lad, called it “the benchmark no one will touch.”

Echoes of Glory: Legacy and the Cost of Immortality

Forty-two years on, Dickinson’s 1983 masterstroke endures as the greatest training achievement in jumps racing history, etched alongside Arkle’s triple crowns and Desert Orchid’s charisma. It propelled him to global fame; by 1984, he was training in California, later California Chrome’s handler in a cross-Atlantic pivot. Yet, the “hell on earth” lingered. Dickinson has spoken openly of the burnout—depression crept in post-Cheltenham, and he stepped away from the UK scene in 1986, citing the “soul-crushing weight” of expectation. “That win saved me, but it broke something too,” he told Thoroughbred Daily News in 2020. Today, at 75, he breeds and consults from Ojai, California, his yard a far cry from Yorkshire’s mud. Bregawn passed in 2001, but clips of that hilltop battle still circulate, inspiring a new generation. As Dickinson puts it, “Greatness isn’t given; it’s forged in the fire. And some fires leave scars you carry forever.” For racing purists, 1983 remains a reminder: behind every fairy tale finish lies a trainer’s unseen torment—and a story worth every blistering stride.