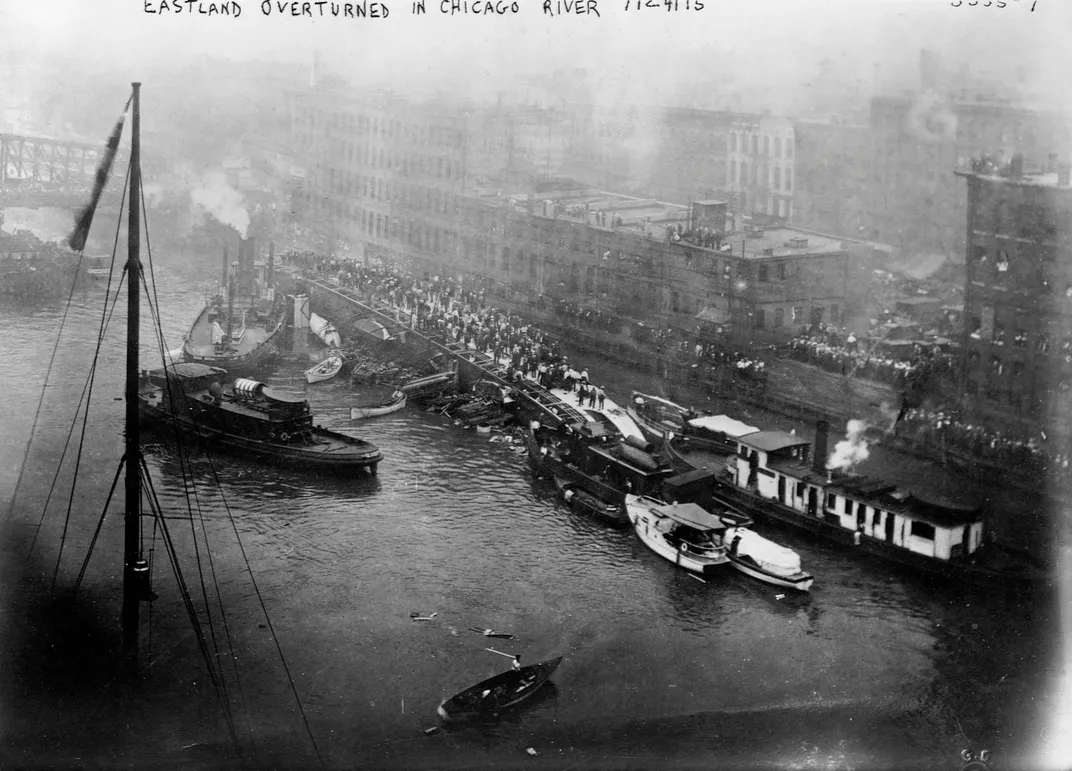

On a drizzly summer morning in July 1915, the Chicago River bore witness to a tragedy that would claim more lives than the Titanic or Lusitania—yet its story remains shrouded in obscurity. The Eastland, a Great Lakes excursion steamer, was set to ferry Western Electric workers and their families on a festive outing across Lake Michigan. Instead, it became the site of the deadliest shipwreck in Great Lakes history, a catastrophe that unfolded in mere minutes, leaving 844 dead in the heart of Chicago.

A Festive Morning Turns Fatal

At 7:18 a.m. on July 24, 1915, E.W. Sladkey, a Western Electric employee, made a desperate leap from the wharf to board the Eastland as its gangplank was raised. The 275-foot steamer, docked along the Chicago River, was packed with 2,573 passengers and crew, its decks buzzing with anticipation. The vessel was one of five chartered to carry workers from Western Electric’s Hawthorne Works in Cicero to a company picnic 38 miles away in Michigan City, Indiana. For many, it was the social event of the year—a rare Saturday off, a chance to dance, socialize, and escape the grind of manufacturing telephone equipment.

Among the passengers were George Sindelar, a foreman, with his wife and five children, and James Novotny, a cabinetmaker, accompanied by his wife and two young children. Young women like Anna Quinn, 22, and Caroline Homolka, 16, donned their finest outfits, hoping to catch the eye of eligible singles. As a band played in the main cabin and passengers jostled for seats on the upper decks, a steady drizzle drove many women and children below to seek shelter.

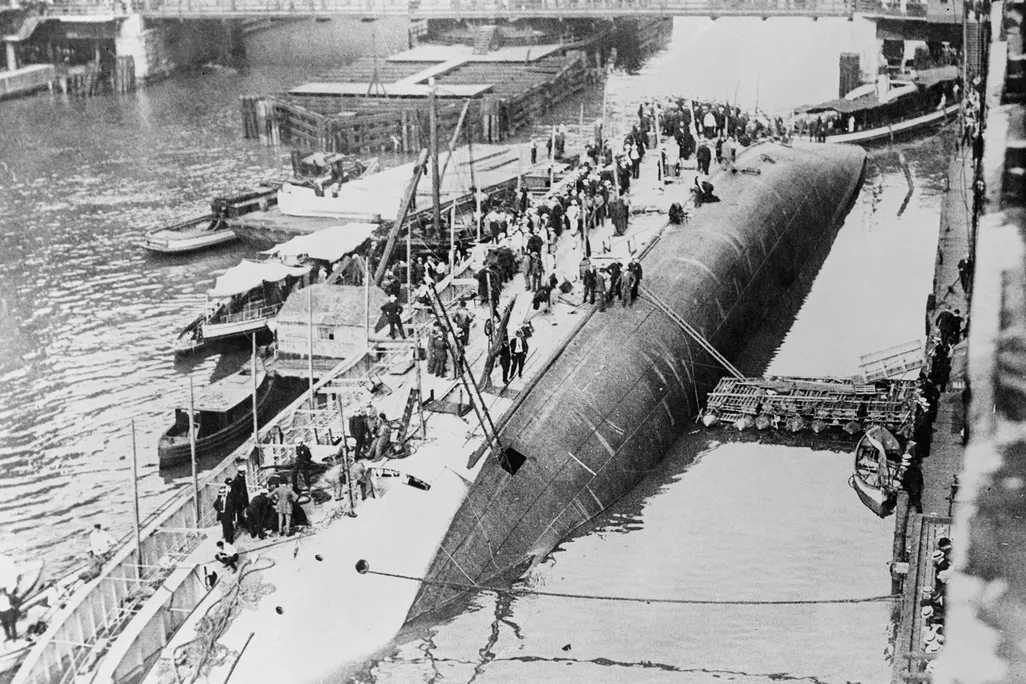

By 7:10 a.m., the Eastland was filling rapidly, with federal inspectors counting 50 passengers boarding per minute. Licensed to carry 2,500 plus crew, the vessel was nearing capacity. But as it took on passengers, it began to list to port, away from the dock. The tilt was subtle at first, unnoticed by the festive crowd but observed by the harbormaster and onlookers on shore. By 7:23, the list worsened. Water surged through open gangways into the engine room, forcing the crew to scramble for safety. Five minutes later, at 7:28 a.m., the Eastland tilted to a 45-degree angle. A piano on the promenade deck crashed to the port wall, nearly crushing two women. A refrigerator pinned others beneath its weight. Water flooded cabins through open portholes.

In two devastating minutes, the Eastland rolled onto its side in 20 feet of murky river water, still tethered to the dock. The Great Lakes’ deadliest shipwreck had begun.

A Flawed Vessel and a Fatal Oversight

The Eastland was a disaster waiting to happen. Built in 1902 to carry 500 passengers and haul produce, it was designed without a keel and relied on poorly engineered ballast tanks for stability. Its shallow draft and top-heavy structure made it notoriously unstable, earning it the nickname “hoodoo boat” among wary passengers. Modifications over the years increased its speed and capacity but further compromised its stability. In 1904, it nearly capsized with 3,000 aboard; in 1906, it listed heavily with 2,530 passengers. Yet safety inspectors, focused only on its performance underway, routinely certified it as safe.

The Titanic’s 1912 sinking had spurred global calls for enhanced maritime safety. In the U.S., the LaFollette Seaman’s Act of 1915 mandated lifeboats for 75 percent of a vessel’s passengers. The Eastland complied, carrying 11 lifeboats, 37 life rafts, and enough life jackets for all aboard—most stowed on the upper decks. But this additional weight, roughly 1,100 pounds per raft and six pounds per life jacket, was never tested for its impact on the vessel’s stability. A Detroit & Cleveland Navigation Company manager had warned Congress that such weight could cause shallow-draft Great Lakes steamers to “turn turtle.” His warning went unheeded.

The Eastland’s metacentric height—a measure of a vessel’s ability to right itself after tilting—was a mere four inches, far below the two to four feet recommended for ships with variable passenger loads. As historian George W. Hilton noted in Eastland: Legacy of the Titanic, the boat “behaved like a bicycle,” stable only when moving. On that fateful morning, docked and overloaded, it was a disaster in waiting.

Chaos and Courage on the Chicago River

As the Eastland rolled, chaos erupted. Passengers on the upper decks were flung into the river “like ants brushed from a table,” wrote Chicago Herald reporter Harlan Babcock. The water turned black with struggling, screaming people. Infants floated like corks; parents clutched children, only to lose them to the current. “The screaming was terrible, it’s ringing in my ears yet,” a warehouse worker recalled. Some passengers, like Sladkey and Captain Harry Pedersen, climbed over the starboard railing and walked across the exposed hull to safety, their feet barely wet. Others weren’t so fortunate.

The riverfront, crowded with 10,000 merchants, customers, and Western Electric workers awaiting other boats, became a scene of desperate heroism. Onlookers leapt into the water, tossing boards, ladders, and wooden chicken crates to aid the drowning. Some crates struck passengers, knocking them unconscious. A man contemplating suicide at the river’s edge reportedly dove in to save lives.

Helen Repa, a Western Electric nurse, heard the screams from blocks away. Arriving at the scene in her nurse’s uniform, she climbed onto the Eastland’s hull, coordinating rescues as bodies were pulled through portholes and survivors were hauled from the water. When a nearby hospital became overwhelmed, Repa ordered 500 blankets from Marshall Field & Company and hot soup from restaurants. She commandeered passing cars to send the less injured home, noting that not a single driver refused her.

By 8 a.m., most survivors were rescued. Then began the grim task of recovering bodies trapped in the portside cabins. Divers worked tirelessly, retrieving women and children who had sought shelter below decks. “The crowding and confusion were terrible,” Repa wrote. Seven priests arrived to offer last rites, but as one reporter noted, “The results of the Eastland’s somersault could be phrased in two words—living or dead.”

A City in Mourning

The disaster’s toll was staggering: 844 passengers, 70 percent under age 25, perished in the Chicago River, just 20 feet from the dock. Entire families were wiped out, including the Sindelars—George, Josephine, and their five children, ages 3 to 15. The Novotny family—James, Agnes, and their two children, Mamie and Willie—also perished. Caroline Homolka and Anna Quinn, the young clerks who had dressed so carefully for the outing, never returned home. Their sisters, Blanche and Alice, waited in vain at a streetcar stop, watching survivors return muddy and broken.

The Second Regiment Armory became a makeshift morgue, with bodies laid in rows of 85. Families filed through to identify loved ones, joined by gawkers and thieves who stole jewelry from the dead. By July 29, all but one body had been claimed: a boy dubbed “Little Feller” by police. His grandmother’s presentation of a pair of brown knickerbockers confirmed him as 7-year-old Willie Novotny, whose entire family had been lost. His funeral, alongside his parents and sister, drew over 5,000 mourners, with a procession stretching more than a mile.

Chicago’s Polish, Czech, and Hungarian communities near the Hawthorne Works were devastated. Black crepe draped countless homes, and the city’s cemeteries couldn’t keep up. On July 28, nearly 700 victims were buried, with 150 graves dug at Bohemian National Cemetery alone. Marshall Field & Company supplied trucks to supplement a shortage of hearses, while 52 gravediggers worked 12-hour shifts.

A Tragedy Buried by Time

The Eastland disaster claimed more passenger lives than the Titanic (829) or Lusitania (785), yet it faded from collective memory. Why? “There wasn’t anyone rich or famous onboard,” said Ted Wachholz of the Eastland Disaster Historical Society. “It was all hardworking, salt-of-the-earth immigrant families.” Unlike the high-profile ocean liners, the Eastland’s victims were ordinary workers, their tragedy unfolding not on the high seas but on a sluggish urban river.

Blame was swiftly assigned. Captain Pedersen and chief engineer Joseph Erickson were detained, partly for their own safety from an angry crowd. Seven inquiries launched within days, with Cook County officials pointing fingers at the U.S. Steamboat Inspection Service. Federal proceedings, overseen by Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, dragged on for 24 years. Erickson, scapegoated for mismanaging the ballast tanks, died during the process, sparing him further scrutiny. Pedersen and the steamship company’s officers faced no criminal charges. Civil lawsuits yielded little for victims’ families, as maritime law capped liability at the Eastland’s value of $46,000, much of which went to salvage and coal companies.

The true culprit, Hilton argued, was the vessel itself—a poorly designed ship made top-heavy by post-Titanic safety measures that were never properly tested. The Eastland’s legacy is a stark reminder of the cost of unchecked regulation and corporate negligence, a tragedy that claimed 844 lives in minutes yet was quietly buried by history.