According to the widely accepted account of human evolution, the human lineage split from that of apes about 7 million years ago in Africa. Hominids (early humans) are thought to have lived in Africa until their first spread to Asia and then Europe about 2 million years ago.

Now, a team of scientists from the University of Tübingen in Germany and the University of Toronto in Canada have updated that narrative. They say the oldest human ancestor may have originated in Europe, not Africa, about 7.2 million years ago—about 200,000 years earlier than previously thought—in two parallel studies published in the journal PLOS One.

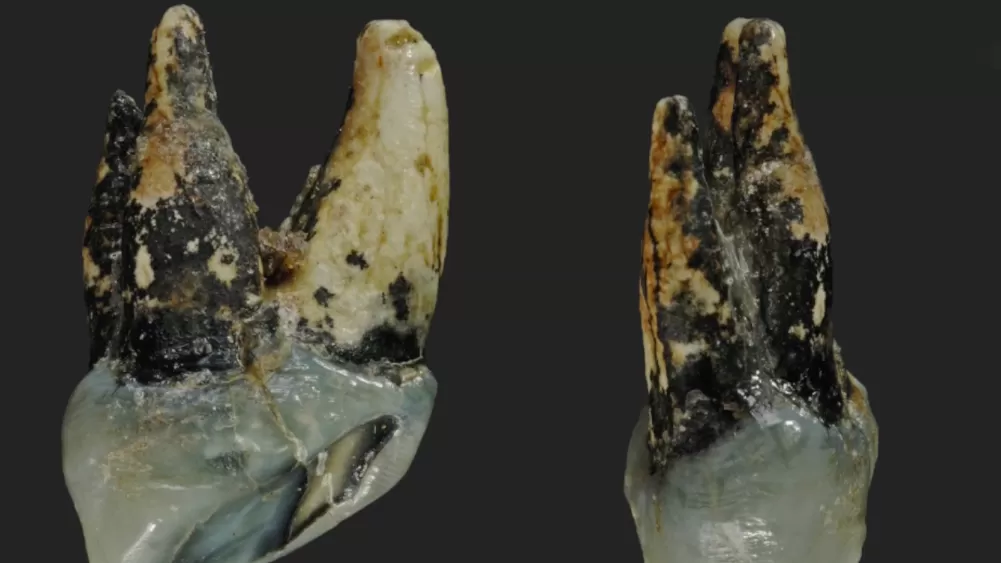

The researchers base their bold hypothesis largely on the analysis of two fossils: a mandible (lower jaw) found in Greece in 1944 and an upper premolar found in Bulgaria in 2009.

The fossils belonged to an ape-like creature known as Graecopithecus freybergi (“El Graeco” for short), which roamed the Mediterranean region between 7.18 and 7.25 million years ago.

Although the fossilized Greek jaw has been around for some time, most scientists considered it a valuable source of information because of its poor condition. “It’s not the best specimen in the world,” David Begun of the University of Toronto, a co-author of the new study, told HISTORY.

“There’s a lot of damage to the surface of the jaw itself and a lot of damage to the teeth, so they’re really hard to see, they’re hard to measure, and it’s hard to tell what they look like.” But when Begun’s colleague, Madelaine Böhme, came up with the idea of using computed tomography, or CT, to look inside the mandible, things got more interesting.

Additionally, analysis of the two fossils showed that some of the roots of Graecopithecus’ bicuspid teeth—what we call premolars—had simplified or fused together to form fewer roots. “This is again something that you only see in humans and our fossil relatives. It’s extremely rare to find in living apes, and you don’t see it in any fossil apes from the same time period,” Begun noted.

In the second companion study, based on sediments in Greece and Bulgaria from that time, Begun and his colleagues found that the climate during the period El Greco lived in those regions would have been similar to that of the dry savannas known to have supported the shift to bipedalism that marked the evolution of early hominins. In fact, it would have been very similar to the climate of East Africa.

If Graecopithecus is in fact a hominid, it would be slightly older than the oldest known human ancestor found in Africa, Sahelanthropus tchadensis. Discovered at a site in Chad, Sahelanthropus is believed to be between 6 and 7 million years old.

Begun stressed that the new hypothesis has no bearing on the later history of modern humans and their emergence from Africa. “That history is completely intact,” he told HISTORY. “It’s about what happened millions and millions of years before that, when the entire human lineage emerged.”

Other human evolutionists are skeptical of Graecopithecus’ newly recognized status as the earliest known hominid. In particular, they question the claim that the shape of the jaw and teeth alone would establish its prehuman status.

“We just don’t have enough evidence to come to that conclusion,” Bernard Wood of George Washington University, who was not involved in the new study, told HISTORY. “It’s entirely possible that one or more fossil apes have roots like these.”

As he pointed out, it is not uncommon for primates to develop the same traits or morphological characteristics independently of one another. “If you asked me how much I would be willing to bet that this is a hominid,” Wood continued, “you would have to persuade me to bet more than a quarter on [that].”

Begun admits the possibility that the shape and size of El Graeco’s teeth may have been independent of early humans, and he says he would like to see more, better-preserved fossil evidence to support this new hypothesis. He nevertheless stands by his and his colleagues’ conclusions about Graecopithecus based on the fossil evidence they have, and he thinks there are probably more.

“I think there’s a good chance we’ll find new sites in the next few years. We might get lucky and find some more teeth and especially some better preserved limb bones that might help us answer this question more definitively.”