It was shortly after noon in the quiet village of Milbrook when a knock on the door of Dr. Ethel Glenfield’s office changed the course of her career, and possibly the entire recorded history of the town. Dr. Glenfield, a veteran historian known for her intimate knowledge of antebellum America, was having tea with her colleague, Dr. Alaric Featherstone, when a young messenger handed her a brown package with no return address.

History Books

What seemed like a normal shipment soon became one of the most shocking and significant discoveries in early American history.

“Who sent this?” Ethel asked, narrowing her eyes. The messenger simply shrugged. Inside the package was a single object: a gleaming daguerreotype—a rare early photograph from the mid-19th century—whose polished silver plate was incredibly well preserved. Beside it, a brief note: “From the archives of the Milbrook Historical Society. Please examine carefully. Clifton House Premises.”

Dr. Featherstone approached, curious. “Clifton? Like the Clifton family from the old Quaker settlement?”

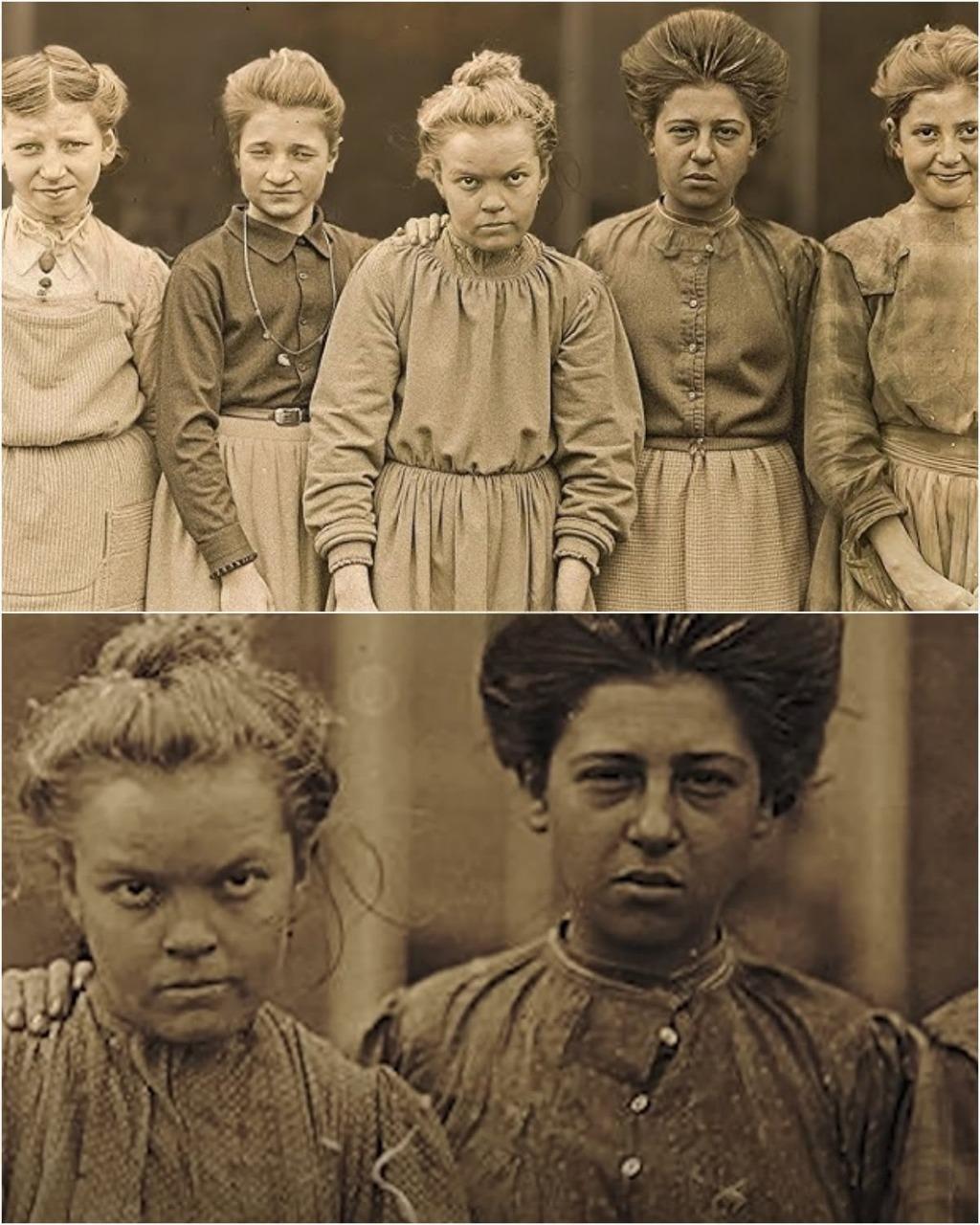

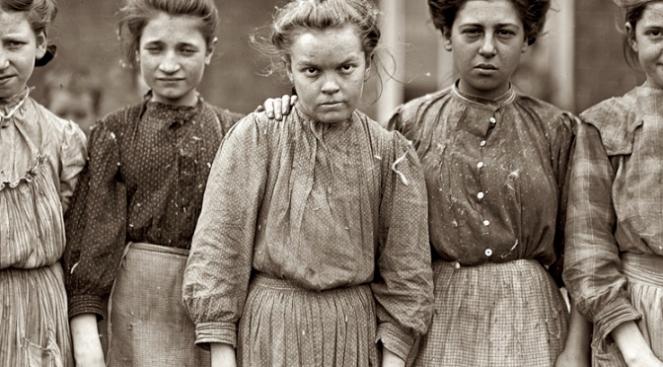

Ethel nodded slowly, already taking a magnifying glass out of her drawer. The photograph, though faded with time, was amazingly detailed. Five girls stood in a stiff row, their dresses worn but clean, their gazes piercing.

The photo that wouldn’t shut up

At first glance, it seemed simple: five sisters, presumably between ten and sixteen years old, posed in front of a worn wooden structure. But upon examining the panel, the two historians noticed something unusual: the girls’ expressions weren’t stiff or formal, but rather marked by something deeper: tiredness, determination, and a quiet sadness.

The girl on the far left wore her brown hair in wild braids and smiled slightly. The two in the middle, presumably twins judging by their features, stood with their shoulders tense and their gaze fixed straight ahead. But it was the last girl, the one on the far right, who gave Ethel pause. Her skin tone was noticeably darker than the others, and her hair was pulled back in a messy bun. She was smiling broadly, radiating hope and innocence. The message was immediately palpable: this family was integrated, something unheard of in 1830s America.

“They’re sisters,” Featherstone said finally, barely above a whisper. “But they’re not all blood relatives. Look at how they hold themselves: protective, as if they’ve already fought battles most people never see.”

Forgotten Records, Hidden Names, and the 1836 Link

Civil War artifacts

Driven by a sudden urge, Ethel pulled her village’s family record book from the shelf. It was a dusty, leather-bound book she had consulted countless times, but never for this occasion. After flipping through dozens of fragile pages, she settled on a familiar name: Clifton, Edna, Lucy, Mabel, Kate, Rose.

Born between 1830 and 1833, they were all daughters of Elijah and Harriet Clifton. Edna, Lucy, and Mabel were biological sisters. Kate and Rose were adopted. Rose, the youngest, was the daughter of a freed slave. An entry in the records read: “Adopted into a Quaker family following the death of her mother in childbirth.”

Together, they formed one of the most progressive households in the region: local activists, musicians, and philanthropists known for helping runaway slaves and caring for orphans. But things took a turn for the worse in 1847. That year, the entire family perished in a fire.

A closer look reveals an even darker secret.

The surface of the daguerreotype gleamed again in the window light. Ethel squinted and returned to her magnifying glass. Then she noticed something in the background: not just a landscape, but people. Children. At least a dozen, perhaps more, partially blurred, but clearly visible. Plainly dressed, with reserved expressions.

“They’re not just posing,” he said slowly. “They’re standing in front of something.”

Ethel enlarged the image on her monitor, complemented by a high-resolution scan she had just completed. The children were unrelated. They had different skin color, height, and facial features. And most importantly, they weren’t there by chance. Their clothes were in tatters. They were standing in neat rows.

Etched near the corner of the photograph was an inscription so faint it was almost impossible to miss: 8:15:1836.

Civil War artifacts

“August 15, 1836,” Featherstone read aloud. That was more than a year before the house fire.

Ethel’s hands shook as she searched through the archived newspapers. A brief article from that same week finally provided context: “Local family shelters 14 children rescued from illegal daycare.” The details remain secret until the trial. The family? The Cliftons.

The truth opened like a latch hidden for centuries: This photograph wasn’t just a portrait, it was proof. It was a visual record of the aftermath of one of the first known child rescues from the era of human trafficking in American history.

Civil War artifacts

Why the photo was commissioned and hidden

Milbrook court records revealed that the daguerreotype was created at the request of the Quaker community to serve as documentation for the trial following the rescue. Fourteen children were found in a cellar hidden beneath a nearby warehouse, starving, abused, and waiting to be transported south. The Cliftons discovered the location following a coded letter from the Underground Railroad.

Rose, barely ten years old, comforted the younger children for three days before the authorities arrived. Mabel and Lucy treated the wounds. Edna spoke to the judge.

The trial was controversial and received little publicity. Three men were convicted and others were released. Weeks later, the Clifton home burned to the ground, an act officially classified as an “accident” but long suspected of being arson.

A legacy written in ashes

The two historians remained silent, overwhelmed by the gravity of their discoveries. “They were murdered,” Featherstone finally said. “Because they were telling the truth.”

Ethel nodded, her voice breaking. “And now, almost 200 years later, we can finally tell her story.”

The image was later included in a landmark Milbrook Historical Society exhibit titled “The Clifton Sisters: Unsung Heroines of the Underground Railroad.” In a quiet corner of the exhibit, a plaque listed the names of the five girls, along with those of the fourteen children they had saved.

One visitor later described the moment: “I stood there, looking into the eyes of five young people who knew what was right and chose to act. I realized: sometimes courage doesn’t look like a battlefield. Sometimes it looks like five teenage girls in hand-sewn dresses, caught between evil and innocence.”

Final Thoughts: A Story That Needs to Be Known

This wasn’t just a fragment of photographic history; it was the key to a forgotten legacy of justice, compassion, and profound courage. The Clifton sisters were more than just kind-hearted girls from a progressive home. They were pioneers in child protection and social justice, decades ahead of their time.

And the photo? It was no longer forgotten, buried in an archive. It now bore witness to a truth that generations had overlooked and that the world would never forget.

What would you have done in their place? Would you risk your life to protect those without a voice?

Tell us in the comments and share this story if it moved you. May history remember not only the photo, but also the purpose behind it.