In China, people who were condemned to death by Lingchi for crimes such as horny treason and mass murder in China could be sentenced to death by Lingchi, a cruel direction of execution, in which the victims were dismembered bit by bit until they died.

Warning: This article contains graphic descriptions and/or images of violent, disturbing or otherwise potentially stressful events.

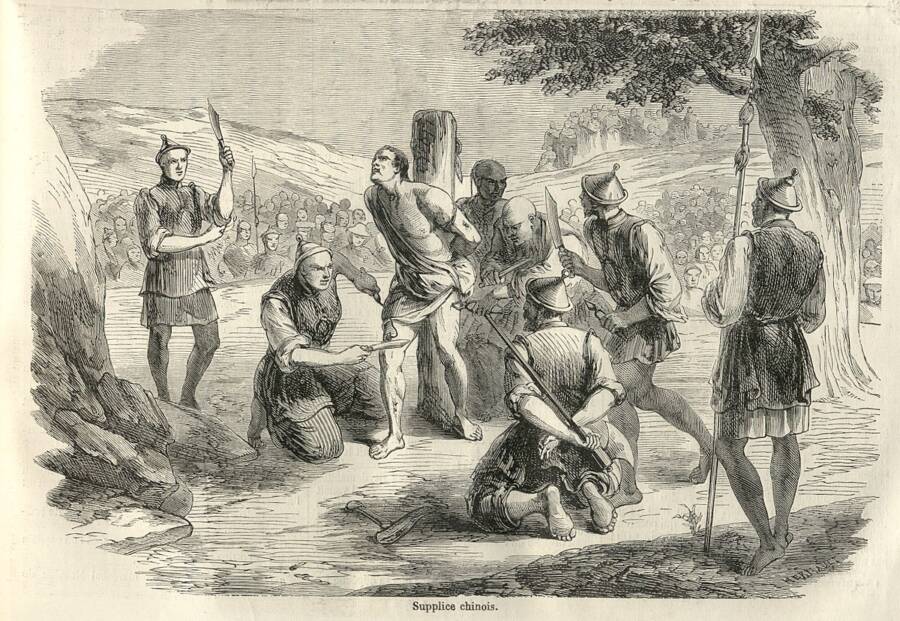

Public Domaineine Illustration from a French newspaper from 1858, which shows the Lingchi execution of Auguste Chapdelaine, a missionary in China.

For about 1,000 years, starting around the 10th century AD, a form of death penalty was characterized in China through its particularly cruel and brutal technology: Lingchi.

Lingchi can be freely translated with “slow cutting” or “death by a thousand cuts”. As the name suggests, it was a lengthy and brutal process in which a handlebar had particularly hideous crime justice by adding a number of cuts into the skin.

In contrast to most of the directions, in which an earlier killing than later, Lingchi’s intention is to carry out a long, slow punishment in order to add as much suffering as possible.

This practice was officially banned by the government of the Qing Dynasty in 1905, but its cruel inheritance continues to this day.

What was Lingchi and how was it done?

The course of the Lingchi was quite uncomplicated. The executioners tied the convict to a wooden post so that he could not move or free from the shackles.

Wellzeome Collectionein rice paper painting from the 19th century, which shows a woman who is slowly cut into pieces.

Some reports, such as the book published by George Ernest Morrison, the author of the book published in 1895„An Australian in China“, mention that the prisoner was given an opium dose before the execution.

The prisoner is tied to a primitive cross; It is always under strong opium influence. The handle stands in front of him and makes two quick cuts over the eyebrows with a sharp sword and pulls the skin off over each eye. Then he makes two more quick cuts over his chest and pierces his heart the next moment. Death occurs immediately. Then he dismantles the body; The humiliation is in the fragmentary figure in which the prisoner must appear in heaven.

As described above, the handle performed cuts into the bare skin, usually starting on the chest, where the chest and surrounding muscles were systematically removed until the ribs were almost visible. Then the executioner worked towards the arms, removed large parts of the skin and released muscle tissue in a painful bloodbath before turning to the thighs, where he repeated the process.

At this point the victim was probably already dead. The executioners then collected the separated limbs and put them in a basket.

Since the Chinese law did not prescribe a certain type of execution, the type of Lingchi varied depending on the region. Some reports report that the punished ones were dead in less than 15 minutes, while other cases apparently lasted hours and the accused had to endure up to 3,000 cuts.

Phgcom/Wikimedia Commonslingchi was also practiced in Vietnam, where Henker committed to the French missionary Joseph Marchand in 1835 with this cruel method.

These details depend on the depth of each incision as well as on the skills of the executioner and the severity of the crime.

According to reports, civil servants sometimes showed pity with people who were lowered by lower offenses and thus shortened their time of suffering. Families who could afford it often had their convicted relatives put up immediately. It was ensured that the first cut was also the last – and they were spared hours of tortuous torture.

Who fell victim to the brutal direction of execution?

Not everyone had to die in such a cruel and unusual way, because Lingchi was only intended for the worst crimes such as betrayal, mass murder, father murder and breath. A man was sentenced to death by Lingchi because he had raped 182 women. And in 1542, according to reports, 16 palace girls were sentenced to brutal death because they tried to murder the emperor.

Another Lingchi report from the 16th century reported about Liu Jins, an eunuch, the Emperor Zhengde served. In 1510 he was sentenced to death because he had snatched too much power to the ruler. According to legend, he suffered over 3,000 cuts within two days before his death. The Beijingers are said to have paid for the pieces of his meat and ate them with rice wine.

In his book published in 1895The Peoples and Politics of the Far EastPublished the English journalist and parliamentary member Sir Henry Norman a section from a Chinese newspaper in which the Lingchi sentence of a woman was described:

Ma Pei-Yao, governor of Kuangsi, reports on a triple poisoning case in his province. A woman who had been beaten by her husband because of her sloppy lifestyle advised herself with an old herbal woman and picked poisonous herbs on the mountain on her instruction. In this way she poisoned her husband, her father -in -law and her brother -in -law one after the other. It was executed in the slow procedure.

While many ancient reports about Lingchi were probably mythologized and fit a sensational western story that described the “wild” practices of the then mysterious Chinese population, a case provided photographic evidence of such cruelty.

National Library of France: Fu Zhuli was the last person who was officially executed by the Chinese government by Lingchi before the method was banned in 1905.

French travelers filmed the execution of Fu Zhuli by Lingchi. He was condemned in 1905 for murder on his Lord, a Mongolian prince. It was the last known execution by Lingchi before the Chinese government banned death from a thousand cuts just a few weeks later.

The abolition of Lingchi as a punishment method

The Lingchi practice was controversial from the start. Chinese citizens spoke against it as early as the 12th century. The poet and historian Lu You wrote a letter to the imperial court of the song dynasty on the grounds: “Even if the muscles of the meat are already removed, the breath of life has not yet been cut off, liver and heart are still connected, see and hear.

The horror of the Lingchi was not only in the painful act itself, but also in their importance for those affected. After the Confucian ideal of the child’s piety or the loyalty to the family, the change in the body of a victim meant that this would not be “complete” in the hereafter.

Thus, this act was both a form of public humiliation and a death sentence, both literally and mentally. This explains why they were only reserved for the most hideous or rebellious offense.

Wellzeome Collectionein Model, which represents the execution method “Death by a thousand cuts”.

Despite the controversy around Lingchi, it was practiced for at least 1,000 years. Although the punishment was officially banned in 1905, there are several alleged reports on their application in the early 20th century.

When Yang Zengxin, the governor of Sinkiang, was murdered in 1928, the man who was held responsible for his death was reported by Lingchi – but he first had to watch his daughter died. In 1936 a communist rebel leader was supposedly executed with this cruel method. After 1905, however, there were supposedly no official Lingchi judgments.

Regardless of when the last Lingchi execution took place exactly, this cruel custom fell out of favor a century ago-but the deed was so shocking that it was not forgotten so quickly.